INTimmortal martyrs

“…Our anaonymous Immortal Martyrs…” —Heinz HAger, The Men with the Pink Triangle, 1972.

As history should convey, LGBTQ+ individuals have long dealt with varying levels of danger and contempt regarding their identities across many cultures, countries, and social circumstances. The gay hunting hysteria of Nazi Germany indicated this danger in one of its worst forms. In The Men With the Pink Triangle Heinz Hager writes, “What in one case is accepted with a smile is completely forbidden when it is openly proclaimed…”(pg. 67). He continues retelling Josef Kohout’s testimony, “When he said goodbye… he assured me that he would always be grateful for my loyalty, above all for my silence.” (Pg. 67) About the sexual relationships between men in Flossenbürg, Germany’s prison camps, Kohout himself recognizes the necessity of his discretion. It is a reclamation of power over his life and personal agency, however little he was afforded at the time.

As I peeled through the writing of Heinz Hager’s 1972 The Men with the Pink Triangle, I encountered a sense of disconnection. The systematic treatment of minority communities in Third Reich Germany, as well as the significantly more insidious violence committed against of gay men within those communities and beyond unearthed a sentiment I have long grappled with.

LGBTQ+ youth are also taught to hide in plain sight, not through shame: but through survival. It is often said that queer people’s connections to their past is uniquely difficult to bridge, as they are the only people who’s youth are not born unto them. Connection to and knowledge from our elders is met with deep absence. In the same way Black Americans continuously experience marginalization and the suppression of culture in white drive spaces. The historic systematic violence and brutality visited upon Black communities across the world has created the same form of absence. In this regard, there are channels of learning through the close knit ties of Black communities. Though, the importance that lineage plays in the inheritance of tradition and identity is still felt viscerally. Many of these lineages have been broken beyond recognition.

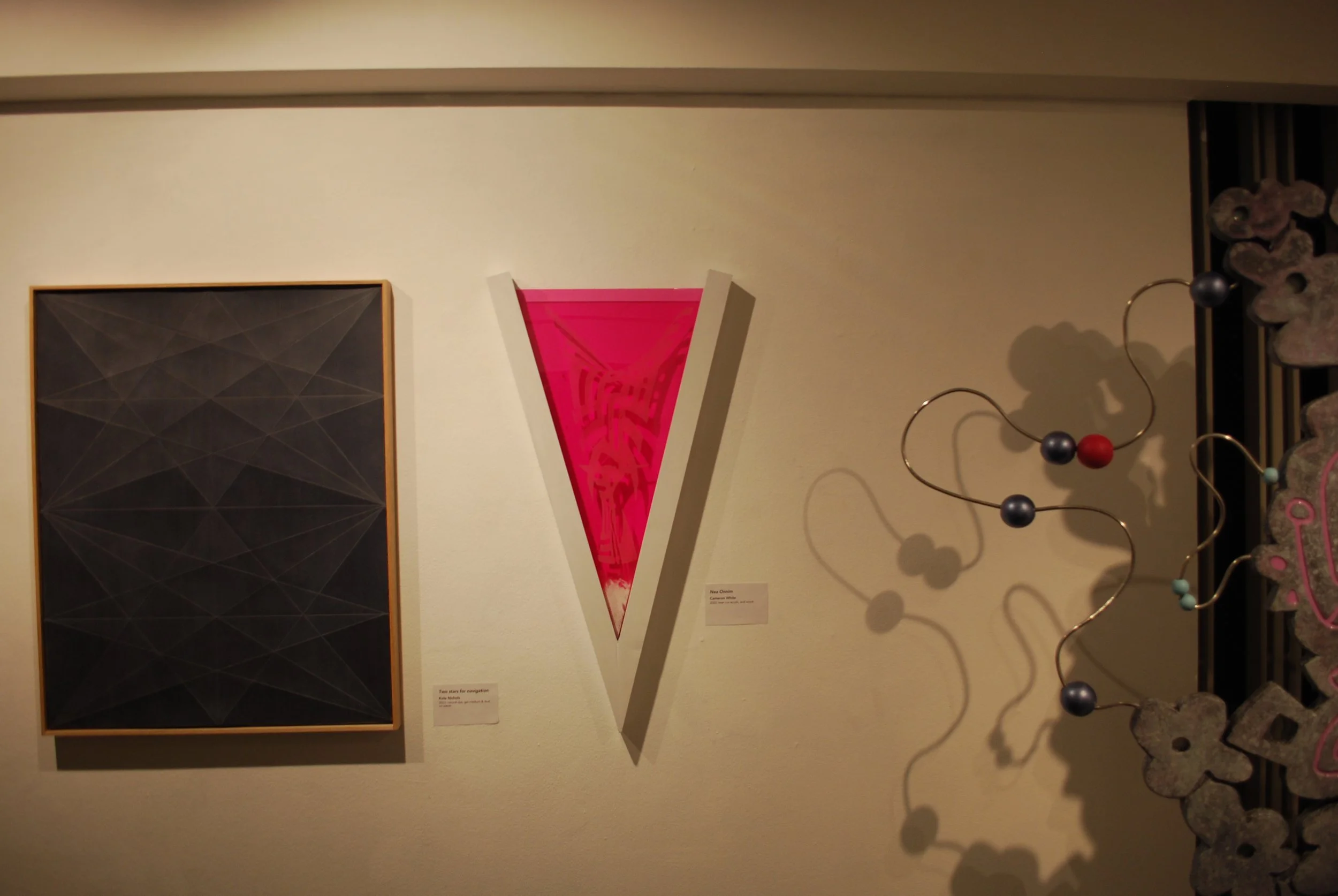

Inspired by Adinkra symbols, a plethora of motifs originating from the Akan and subset of Asante people of Ghana, the pink triangles have were conceptualized through my foothold in both communities. The Akan Sankofa translates from Twi to “go back and get it.” It serves as a reminder of the importance of the past instilling a duty of learning in the people who follow its creed. This symbol, among many others, remains a prevalent cultural motif for the Black diaspora. To seek out my own history, is to reckon with the experiences of Black and queer peoples and uncover the ties that have historically bound them in solidarity. Immortal Martyrs was born out of my intersectional existence as a Black American queer person as a defiant act of archival, public intervention, and personal exploration of the transgressions against those linked identities within the barriers of the greater Atlanta metropolitan area.